Blog & Resources

Looking for my thoughts on everything from bioethics to movies? You came to the right place. And while you’re here, check out my free downloadable resources.

Sign up to be notified when new posts release.

Artemis of the Ephesians: A Conversation with Wayne Stiles

Our understanding of Artemis of the Ephesians at the time of the apostle Paul has, I believe, implications for how we read 1 and 2 Timothy. Recently I spoke with Wayne Stiles with Walking the Bible Lands about my research on this goddess and her influence, especially in the Province of Asia. You can watch our conversation in this video.

Right now I'm working on two books right now relating to the Ephesian Artemis and the ramifications for women and our understanding of first-century backgrounds—one a work of fiction and the other, an academic book.

My readers can get a free video series on Jesus's life from Walking the Bible Lands courtesy of Wayne.

Peter to Wives: Put Off, Put On, Watch This

My Engage post for the week:Instead of telling first-century wives to submit because they are inferior, as many believed at the time, Peter urges them to be submissive for a very different reason—so that their husbands might find true life (1 Peter 3:1). Peter encourages these wives to be subversive (keep worshiping Christ—which hubby may not like) in a cloak of respect (submit to your husband) so as to achieve a good end. Here is his rationale:In the same way, you wives, be submissive to your own husbands so that even if any of them are disobedient to the word, they may be won without a word by the behavior of their wives, as they observe your chaste and respectful behavior. And let not your adornment be merely external—braiding the hair, and wearing gold jewelry, or putting on dresses; but let it be the hidden person of the heart, with the imperishable quality of a gentle and quiet spirit, which is precious in the sight of God. For in this way in former times the holy women also, who hoped in God, used to adorn themselves, being submissive to their own husbands. Thus Sarah obeyed Abraham, calling him lord, and you have become her children if you do what is right without being frightened by any fear (1 Peter 3:1–6, NAS).In Peter’s day, a wife was considered property, could not speak for herself in a court of law, and (of key significance here) was expected to worship the same god or gods as the householder.A number of Peter’s readers have husbands whom he describes as “disobedient to the word.” Doubtless, some of these wives in his readership are from households where Hecate or Apollo are worshiped, and great harm could come to these women if they spoke in a cocky way about Zeus or trash-talked Leto, false as these gods are. Even Paul when speaking of Artemis in Ephesus, was described as not blaspheming the goddess (Acts 19:37).Instead, in such a world, the wise believing wife is told she should show her fear of God by remaining quiet about her faith, while also remaining fiercely loyal to Christ (a radical idea) “without being frightened by any fear” (1 Pet. 3:6). Notice Peter does not tell wives to stop worshiping Christ and obey by worshipping their husbands' gods, which is what one would expect a good Roman family man to say. We must read between the lines to see how clever (indeed, subversive) he is in his advice to submit. It’s what he doesn’t say that makes it so interesting. He's telling wives to submit to husbands, but he's expecting these wives to keep worshiping Christ, whom the "disobedient" householder would object to her worshiping. But she is to keep quiet about it and actively seek to change his loyalty to his god with her own character.The writer of these words is not a man out to put down women; he is looking out for wives’ interests while working within existing structures and having as his first priority the advancement of the gospel that equalizes.The word translated “reverent” in this passage is not actually an adjective, but is the object of a prepositional phrase “in fear.” A wooden translation would be “as they observe your pure conduct in fear.” And the fear or respect is actually not directed toward the husband here. In Peter’s usage, such fear is always directed toward God—not in a terrified way, but in a reverent one. The point here, then, is not actually that the wives should be reverent toward their husbands, but rather that these women should live purely “in the fear of God” as part of their silent witness.Peter goes on to use the image of adornment three times within the short space of three verses to make his case. One reference is to the wives’ external signs of status (3:3). One is to their internal character (v. 4). And one is to the adornment of the past holy women of God (v. 5).Put off externals. Peter begins his argument by saying, “Let not your adornment be external” (v. 3). Many translations have added “merely external,” which suggests that these wives could have some external adornment. Other translators have rendered the text as saying, “Let not your adornment be external only.” But the modifiers “merely” and “only” are not in the original.After telling wives not to adorn themselves externally, Peter immediately specifies the sorts of external adornments he means: braiding the hair, and wearing gold jewelry, or putting on apparel. And Peter’s readers understand he is not telling wives to be plain.To understand his meaning when it comes to braids, jewelry, and dresses, we must bear in mind that the honorable Greco-Roman wife wore the signs of her social status on her person. Many think the apostle’s earlier reference to “pure and reverent conduct” (v. 2) suggest he is concerned primarily with sexually provocative dress. But while dressing suggestively would be inappropriate, Peter appears to have more of a class than a moral concern in mind when mentioning braids, jewelry, and apparel.In the first century, every single piece of gold, diamond, and pearl was real. And wearing her external status was the opposite of what Peter envisioned for reverent wives. Usually letters like Peter’s were addressed only the people with social power—the householders. But in his epistle he directly addresses wives and slaves. (Radical! Elevating!) And the same person who elevated those with less social power by addressing them directly wanted godly wives to dress in a manner devoid of anything that would suggest superiority.Put on internals. Instead, Peter urges the wife in his audience to adorn themselves with something far more precious—something that is of great value to God—a gentle and quiet spirit. By coupling “gentle” with “quiet” Peter intensifies the virtue. And his hope is that the wife’s virtue will reveal a different value system to her husband and others in her sphere of influence.The spirit Peter envisions is not something the wife takes on and off as she would gold or apparel. Rather, it is permanent ornamentation, thus imperishable. Back in chapter 1, verse 7, he wrote that gold was “passing away”; in 1:18, he described gold and silver as “perishable.” And these references that appear only a few chapters earlier inform how he wants readers to understand his use of “imperishable” in this passage as applied to the wife’s virtue. The gentle and quiet spirit is the only kind of beauty that a woman can put on that will never be taken from her. It will not wrinkle or sag with age. Humans consider gold precious. The God who will one day pave the streets of his city with it considers something else far more precious—character.The “gentle and quiet” language has at times been mistaken both as a criticism of extroverted women, and also as a source of pride for introverts and/or husbands married to them. Yet by describing the godly woman as having a “gentle, quiet spirit,” Peter is not saying extroverted women have less godly personalities than introverted women. Nor is he saying that women with spiritual gifts that involve speaking should stop exercising these gifts and remain silent. The gentle, quiet “spirit” here is not a personality type; it’s a virtue. And “putting on” such a virtue, especially in the face of injustice, is an equal-opportunity option.The quietness Peter has in view is also not absolute silence. Rather, it is a refraining from speaking “words” the wife might think it wise to say to win her husband (3:1). Peter’s instruction in many ways takes the pressure off her to craft the most winsome argument that will lead her husband to conversion. Her silent spirit allows the Holy Spirit to do his work. This wife's hope must not be in herself, but in God.Watch this. Peter returns to the adornment image to give a rationale for this counsel about wives’ internal apparel. He writes,“For in this way [that is, internally] in former times the holy women also, who hoped in God, used to adorn themselves, being submissive to their own husbands. Thus Sarah obeyed Abraham, calling him ‘lord’ . . . (3:5–6).Once again the word “adorn” has appeared, and in this context it is a continuing action on the part of holy women. These matriarchs of the faith hoped in God—the very thing Peter wants all his readers to do. His readers can draw hope from the fact that someone ahead of them in the race has faced the same challenges and finished well.

Is Peter Insulting Women? (Part 1)

My Tapestry post for the week:

A Week in the Life of Corinth

The total effect is the mirror of what happens when fictionwriters don’t know about biblical backgrounds, so they write the Esther storyas a romance. Here a biblical scholar has not mastered the art of writtenstorytelling. And we need both excellent storytelling and good background expertise.(Ben-Hur is an example of a work thatweds the two fields in a way that gives readers a story for the ages.)

|

| Paul would have been familiar with the "bema" or judgment seat in Corinth. |

Samaritan Woman: Stay Away from Me?

Ireceived a question this week from a former student, Vernita, about theSamaritan woman, whose story John records in the fourth chapter of his Gospel.

Backgrounds Matter

Today was my day to blog over at Tapestry, the Christian Women in Leadership blog. My topic was first-century backgrounds. Here's what I wrote...

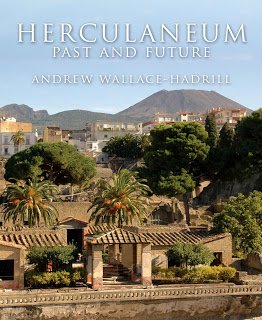

The Death of Two Cities

We’ve all heard of Pompeii, the city buried when Mt. Vesuvius blew its top in A.D. 79. But a much smaller number of us have heard of Herculaneum. To be honest (I’ll show my ignorance here), I'd never heard of it till I started checking out info on its buried sister city a year ago. When Mt. Vesuvius erupted around 1 PM that autumn, the southeast wind blew pumice and ash over Pompeii, burying it. But it wasn’t till after midnight that night in nearby (and closer to the summit) Herculaneum that a flow of heated gas rolled down the mountain and fried everything in its path. For years experts thought everybody must have escaped in Herculaneum, because archaeologists found only a few skulls. But within the past few decades, a huge number of human remains have been discovered down at the waterfront. Apparently most people fled to the harbor and hid under the arches holding up the boardwalk. Shoulda been safe, huh? Well, not when a rolling 700-degree fire descends on you. A cool thing about Herculaneum is that the fire was hot enough to kill (bad), but not so hot as to incinerate everything (good). This means that two thousand years later, archaeologists are uncovering carbonized wooden beds and house beams as well as entire loaves of bread! Many of the emblems of daily life have survived. Totally rare. And fascinating.

We’ve all heard of Pompeii, the city buried when Mt. Vesuvius blew its top in A.D. 79. But a much smaller number of us have heard of Herculaneum. To be honest (I’ll show my ignorance here), I'd never heard of it till I started checking out info on its buried sister city a year ago. When Mt. Vesuvius erupted around 1 PM that autumn, the southeast wind blew pumice and ash over Pompeii, burying it. But it wasn’t till after midnight that night in nearby (and closer to the summit) Herculaneum that a flow of heated gas rolled down the mountain and fried everything in its path. For years experts thought everybody must have escaped in Herculaneum, because archaeologists found only a few skulls. But within the past few decades, a huge number of human remains have been discovered down at the waterfront. Apparently most people fled to the harbor and hid under the arches holding up the boardwalk. Shoulda been safe, huh? Well, not when a rolling 700-degree fire descends on you. A cool thing about Herculaneum is that the fire was hot enough to kill (bad), but not so hot as to incinerate everything (good). This means that two thousand years later, archaeologists are uncovering carbonized wooden beds and house beams as well as entire loaves of bread! Many of the emblems of daily life have survived. Totally rare. And fascinating.

Until last week, I used a 1966 book about Herculaneum—the most recent English-language resource—to help me reconstruct the eruption for a novel I’m writing. But then I heard about Andrew Wallace-Hadrill’s 2011 release on Herculaneum. He’s a mega-expert on Herculaneum, who was interviewed on PBS’s home video about Herculeneum in their “Secrets of the Dead” series. I ordered his book on Amazon for $37 (hardcover), expecting a reference work. But what arrived was a gorgeous coffee-table book, chock full of foldout pictures, diagrams, and fascinating prose. Plus it has all the latest info, some of which completely contradicts earlier assumptions, which means I’m rewriting a few scenes. But not matter—this book is a gold mine. We have assumed in the past that Pompeii showed us the norm of first-century life. But with the past decade of discovery in Herculaneum, we now know that Pompeii was more populated and urban, and Herculaneum was smaller and wealthier. It’s city vs. town, urban metropolis vs. resort spot. Pompeii had the brothels; Herculaneum did not. Pompeii had lots of graffiti; Herculaneum did not. Picture the difference between Vegas and Pebble Beach and you get the idea about how much we should extrapolate about "norms" from one city's evidence.

I, Claudius

A Good One for Your List

If you want to learn more about the first century Greco-Roman world, you can wipe the dust off a history book and inch your way through the prose. Or you can pick up The Lost Letters of Pergamum, an engaging 200-page work of historical fiction in which the author uses the literary technique of story through correspondence as an entrée into the ancient world. In this work readers catch first-person glimpses of life in an honor/shame society as they read “newly discovered ancient letters.”

If you want to learn more about the first century Greco-Roman world, you can wipe the dust off a history book and inch your way through the prose. Or you can pick up The Lost Letters of Pergamum, an engaging 200-page work of historical fiction in which the author uses the literary technique of story through correspondence as an entrée into the ancient world. In this work readers catch first-person glimpses of life in an honor/shame society as they read “newly discovered ancient letters.”

Readers meet Antipas, a Roman civic leader who has encountered the writings of Luke, the physician who researched and wrote an account of the Galilean’s life for someone named Theophilus (see Luke 1). Luke's history sparks Antipas's interest, and they engage in a correspondence about it. Those of us reading their accounts learn about gladiatorial contests, storms at sea, travel by foot, poverty, wealth, social class designations, slavery, persecution, and honor.

Unlike some writers of historical fiction, author Bruce Longenecker is careful to draw a meticulously accurate picture. And for those who want to go beyond enjoying the story to know what’s “true” and what’s “made up,” notes in the back of the book reveal all.

Yes, The Lost Letters of Pergamum provides readers with a context for understanding the ethos of the ancient world. But did I mention it’s also a good read, a gripping story? The surprise ending left me weeping. Four stars.