Blog & Resources

Looking for my thoughts on everything from bioethics to movies? You came to the right place. And while you’re here, check out my free downloadable resources.

Sign up to be notified when new posts release.

Church History: What Do We Learn about Women in Public Ministry?

“It was the feminist teachings of the past few decades that first spurred Christians to try to argue for [women in public ministry]. Like it or not, the two schools of thought are intertwined.” – Christian blogger

“The role of women in church ministry was simply not a burning question until it asserted itself in recent decades in conjunction with the modern women’s movement” – Men and Women in Ministry: A Complementary Perspective,p. 20

When I took some doctoral courses in history, I read numerous primary documents which revealed that the question about women in public ministry in the church has been burning since long before the U.S. Women’s Movement. So, I set out to determine when it actually started.

I thought maybe it began with the American and French Revolutions with the cry for individual rights. But then I read documents like the pamphlet that Margaret Fell Fox (think George Fox of Quaker fame) wrote in 1666 titled “Women’s Speaking Justified, Proved, and Allowed by the Scriptures.” And I saw art like the above engraving dated to 1723 that features a woman preaching.

So, I looked earlier. Maybe the Reformation started it, I thought—with its emphasis on the priesthood of all believers and the involvement of early women reformers like Katherina Zell.

But then I found writings like those of Christine de Pizan, who was born in the 1300s. Her work, The Book of the City of Ladies, presents a positive view of the Bible as she cites examples of biblical women, carefully selecting those who challenge her culture’s misogynistic ideals.

I kept going. Here are some samplings from the first nine centuries:

Pope PaschalI [Rome – West, AD 822] had a mosaic made of his mother, Theodora, labeled with the title “episcopa” (bishop). An inscription in another place in the same church (St. Praxedes) also describes her as “episcopa.”

Council of Trullo, Constantinople [Turkey – East], AD 692, canon 14. The Council speaks of “ordination” [cheirotonia] for women deacons using the same term used for ordination of priests and male deacons.

Synod of Orleans AD 533, canon 17 [France – West]. Attended by 32 bishops. Here’s a quote from the Synod: “Women who have so far received the ordination to the diaconate against the prohibitions of the canons, if it can be proved that they have returned to matrimony, should be banned from communion.”

St. Remigius of Reims [AD 533 AD, France] makes mention of his daughter, the deacon(ess) Helaria, in his will.

Synod of Epaone, AD 517, canon 21 [France]. “We abrogate the consecration of widows whom they call ‘deaconesses’ completely from our region.”

Ecumenical Council of Chalcedon, [East – Turkey] canon 15, AD 451. An earlier minimal age of 60 years for women deacons was relaxed to 40 years. The earlier practice was based on 1 Timothy 5:9: “Let a widow be enrolled if she is not less than sixty years of age.”

Synod of Orange, [West – France] AD 441, canon 26. Attended by 17 bishops. “Altogether no women deacons are to be ordained. If some already exist, let them bend their heads to the blessing given to the (lay) people.”

First Council of Nicea, [Turkey – East] canon 19, AD 325. Deacon(esse)s are mentioned in passing in a canon referring to the reconciliation of ex-members of the sect of Paul of Samosata (AD 260–272). Paul, patriarch of Antioch, denied the three Persons of the Trinity: “In this way one must also deal with the deaconesses or with anyone in an ecclesiastical office.”

Back, back, back I went. And each century sent me to an earlier one to find when it started. Eventually, I concluded that evidence for orthodox Christians affirming women in public ministry started on the day of Pentecost.

So what happened after that? What led to the changes?

This fall, I have been camping out in the first six centuries of church history, tracing the office of widow, which I first saw years ago mentioned in my Greek lexicon (BADG) as the last entry for the meaning of “widow.” It appears that the early church did have such an office, along with that of deacon(ess).

In 1976, a scholar in Belgium named Roger Grayson published a book titled The Ministry of Women in the Early Church with The Order of St. Benedict. It was translated into English and published by The Liturgical Press—not exactly feminist credentials. And he traces the offices of widow and deacon(ess) through the early centuries of the church. After surveying the data, he draws this conclusion: “Up to the end of the nineteenth century, historians of the early Church often identified deaconesses and widows as if these two different titles corresponded, for those who held them, to the same function.” In other words, historians conflated the two offices of deacon(ess) and widow. He goes on to note that “since deaconesses and widows obviously corresponded to quite different institutions, one can only wonder, after a close study of all the evidence, at the persistence of such an error” (110). That is, how is it possible that—in light of such overwhelming evidence—the error of conflating the two so stubbornly persisted?

Before exploring the answer, we need to keep in mind two details:

First, there was no female form of the word “deacon” in the early church and for some centuries to follow, in the same way that the word “teacher” in English does not indicate gender (e.g., teacher/teachess). That’s why I’m denoting uses of the word in this post as “deacon(ess)” unless the word “deaconess” appears in someone else’s quote.

Second, I’m using “office” to refer to positions in the church that have come with qualifications of character, as contrasted with “gifts,” which are bestowed by the Spirit on all believers.

Now then, apparently, historians expanded their tools of analysis beyond church fathers’ manuscripts and pronouncements by councils to include liturgies and tombstones for mentions of “deacon(ess)” in the early church. Yet in some places, we don’t even begin to find mention of “deacon(ess)” till the third century because the prominent office in that geographical location was “widow.” And the office of deacon(ess) looked different from the office of “widow” in the first centuries. And how the clergy was even configured varied by location (east as compared with west), century, and local council.

As Grayson has noted, such historians were not looking for references to the office of “widow.” Thus, some concluded that women’s membership in the clergy was a late development. Because if someone is thinking the word “widow” refers only to a woman bereft of her husband rather than also including an office rooted in 1 Timothy 5, that researcher can see a tombstone that says “a widow of the church” and miss that he or she is looking at the very evidence sought. Consequently, some historians have drawn faulty conclusions.

Grayson summarizes: “One thing is undeniable: there were in the early Church women who occupied an official position, who were invested with a ministry, and who, at least at certain times and places, appeared as part of the clergy. These women were called ‘deaconesses’ and at times ‘widows’” (xi).

May I remind the reader that Grayson was writing in the 1970s for a Roman Catholic publisher in a different country? This is not US feminism in the Protestant church talking.

The history of women in public ministry reveals that it started at the beginning. And practices in the East differed from those in the West.

In some locations, the widow was 60 years old or older, and the virgin was younger. Tertullian [b. AD 160, N. Africa] ranked the widows among the clergy, and spoke of seats being reserved for them. In his work titled De virginibus velandis (9:2–3) he wrote with displeasure, “I know plainly that in a certain place a virgin less than twenty years old has been placed in the order of widows (in viduatu)!” Clearly, in this instance a “virgin” is not simply a maiden, but someone consecrated to Christ for vocational ministry.

In the East, deacon(esse)s catechized women considering conversion, assisted at baptisms for women converts, and distributed the Eucharist to female shut-ins. The ordination rites for deacons and deacon(esse)s were almost identical.

By the third century in the West, the office of widow was described as a thing of the past. Grayson notes that whenever the Alexandrians [i.e., Egypt—West] mentioned women deacons or widows, they referred to these as offices of the past, not active in the present. Both Clement and Origen occasionally recognized that women were placed in the service of the church in the time of the apostle Paul, but these men did not indicate that the office survived.

In the fifth century the Testamentum Domini Nostri Jesu Christi, probably from Syria [East], devoted four long chapters to widows. It referred to the “ordination of widows,” in two instances using the same word employed for clerics in major orders.

Later in the East, the relationship between widows and deacon(esse)s makes a reversal, and widows, who had once supervised deacon(esse)s become subject to deacon(esse)s.

Eventually, offices in the East have the same labels as in the West, but in the West they are merely honorary. The East was actually more conservative and segregated, so we find more mentions of workers doing ministry focused exclusively on women. For men to do so would have been considered an encroachment beyond their boundaries. But as infant baptism eventually replaced adult baptism, the need for someone to assist with female adults being baptized (often nude to symbolize “rebirth”) disappeared.

What other factors besides infant baptism led to the tapering off of women in ordained ministry?

These reasons emerged from the writings:

Rise of the all-male priesthood in the pattern of the Old Testament. (What happened to the NT priesthood of all believers?)

A return to Old Testament temple practices—especially after Constantine, with church buildings and the clergy/laity divide—such as barring menstruating women from worship. (What happened to the veil being ripped and the Law being replaced by Christ?)

Anthropology. Some of the church fathers held to Greek views (think Aristotle) of woman’s nature, which would be unanimously denounced today. (Why pattern the church’s practice after the thinking of a pagan philosopher?)

Misogyny. Many believed women were weak, fickle, lightheaded, of mediocre intelligence, and a “chosen instrument of the devil.” (Does that sound at all like Jesus?)

Regardless of what conclusions we draw about what of today’s practices should build on tradition and what need to go, we must never think that the US Women’s Movement was ground zero for the public, vocational, ordained ministry of women in the church. When we say such things, historians roll their eyes. If we talk only of what the church fathers were doing without including what the women were doing, we are talking only about “men in church history,” not “church” history.

It was not the feminist teachings of the past few decades that first spurred Christians to argue for women in public ministry. Like it or not, it started at Pentecost. And it will be fully realized in the eschaton (Joel 2, Acts 2).

Bonhoeffer: Pastor, Martyr, Prophet, Spy

Why I Study Greek and First-Century Ephesus

"I would say that a clear understanding of the character of earliest Christianity—its beliefs, its practices, its struggles and challenges—are essential if we are to understand who we are as Christians and who we ought to be and to be about. The church today is suffering from a sort of amnesia; it has forgotten the rock from which it was hewn, and so it fails to understand its own identity. The past, as Lightfoot would say, is not mere prologue; it is the foundation of our faith and on it we must stand. Lightfoot reminds us again and again that history matters, that nothing can be theologically true that is historically false, that a gnostic sort of spirituality that divorces itself from the original Greek text and context of Acts is not a Christian approach to spiritual formation but a heresy against which the church fathers fought vigorously."

—Ben Witherington III, IVP Academic Alert 23, no. 3 (Winter 2015), p. 4.

Politics: A Biblical Approach

It's my day to post on Tapestry. Here's what I said...

In an election year with conventions, platforms, and speeches in the news, we have a unique opportunity to converse in the public square. Having a Christian worldview should affect how we think and interact about politics. Here are some suggestions:

· Be intentional in how you present history. The biblical worldview that once helped shape society has given way to relativism and atheism. Pornography has invaded our homes, including those of our pastors. How the world has changed! Nevertheless, during the days when most could name the Ten Commandments, some Americans were less than full citizens under the law, and lynching was common. Women had no voting rights, nor could they serve on juries. Only a limited view of our history says we have been on a constantly downward slide since the days of the Puritans. My grandfather deserted my grandmother in the 1930s, leaving her with a small child in a day when the church judged the divorced. I met a woman last week who was date-raped in the 1960s, and she had to go into hiding to keep her church from finding out. The Christian sub-culture in America was not so long ago a dangerous place to be broken. Thank God that despite some declines we have also seen some improvements. The presentation of US history as only declining without qualification can sound racist and sexist—ways that are not of Christ.

· Eschew offering false fear and false hope. To offer any candidate as the solution for a country’s ills is to set up a false messiah. A candidate might have what we consider a better approach to healthcare or abortion rights or unemployment, but no candidate can “save our country.” We tend to err in the extremes of fear mongering or offering utopia. Neither approach lines up with the truth.

· Recognize the limits of politics. Christ, not legislation, is the ultimate solution for culture. Only when His kingdom comes shall His will be done on earth as it is in heaven. In the days when abortion was illegal, one of my relatives found a way to have one. Civil law, important as it is, is external and limited in its scope. But Christ brings new life from the inside out. While the law does help provide moral structure, the Christian’s hope for change lies in a “someone,” not in a secular system. Who does or doesn’t inhabit the oval office is of little consequence compared with the change available in Christ. Lobbying and boycotting can bring some external results, but they cannot effect inner change.

· Remember your roots. The Chick-fil-a fiasco reminded the world that the Christian sub-culture in America is large, powerful, and refuses to be pushed around. But the Christian sub-culture in most other parts of the planet was and is politically and socially weak—even powerless. Reading the New Testament helps us see the church can still flourish when the state hates Christians; even a Nero in power cannot prevail against the church. While in the States we have much social power that gives us freedom to worship in public, pray in public, and broadcast our worldview on the radio (wonderful freedoms!), such acceptance of Christianity also brings some unique temptations. We have at times been so cozy with politicians that people now tend to associate Christianity with one political party. A magazine I receive for editors lists words that have changed in meaning, and it listed a new primary meaning for the word “Christian” as “one associated with a right-wing political party.” Rather than perceiving that we address the greed and immorality rampant in both parties, the world sees us as too cozy with one kind of power. Our love for politics and politicians can blunt our ability to speak and even to hear the truth. ("If we acknowledge the bad in our favored party, the other party's guy might get elected.")

In the words of John MacArthur, “America's moral decline is a spiritual problem, not a political one, and its solution is the gospel, not partisan politics.” I encourage all Christians to involve themselves in serving to make the world a better place in any way possible. But we must be biblical and realistic in how we think and talk about what politicians and legislators can do. Jesus, not Caesar, is the answer for the world today. Let us render unto God the things that are God’s.

Documentary Storm

It's Not Some New Debate

The cover story for this month's issue of Christianity Today relates to the 400th anniversary of the King James Version of the Bible. In "A World without the KJV," Mark Noll writes, "American history might have skipped several dark chapters if the KJV had not become the dominant Protestant translation. Many of the worst chapters concern slavery. The KJV regularly rendered the Greek word doulos as 'servant.' 'Servant' and the more accurate translation, 'slave,' were already differentiated in the 16th century and became even more so as time passed… These passages regularly trumped efforts to use biblical reasoning rather than straight biblical quotation….

The cover story for this month's issue of Christianity Today relates to the 400th anniversary of the King James Version of the Bible. In "A World without the KJV," Mark Noll writes, "American history might have skipped several dark chapters if the KJV had not become the dominant Protestant translation. Many of the worst chapters concern slavery. The KJV regularly rendered the Greek word doulos as 'servant.' 'Servant' and the more accurate translation, 'slave,' were already differentiated in the 16th century and became even more so as time passed… These passages regularly trumped efforts to use biblical reasoning rather than straight biblical quotation….

"Women made similar complaints throughout the 19th century. What we would call feminist objections were of two kinds. Some objected to the whole character of biblical revelation, in whatever version. Many contributors to Elizabeth Cady Stanton's The Woman's Bible of 1895 made such complaints. Others were more concerned with issues of translating the words for "man" and "mankind," issues that still incite debate. In 1837, abolitionist and suffragist Sarah Grimké had these issues in mind when she professed her entire willingness to live by the Bible, but also her ardent desire for a new translation: ‘Almost every thing that has been written on this subject, has been the result of a misconception of the simple truths revealed in the Scriptures, in consequence of the false translation of many passages of Holy Writ …. King James's translators certainly were not inspired. I therefore claim the original as my standard, believing that to have been inspired."

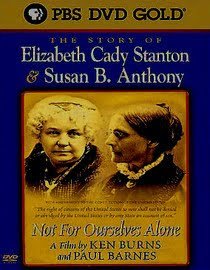

Tonight I watched the three-hour PBS documentary, “Not for Ourselves Alone: Elizabeth Ca dy Stanton & Susan B. Anthony” (1999). The film tells the story of these two friends who worked together decade after decade to obtain the vote for women, but who did not live to see their dream become reality. In fact, they died before my grandmother was born.

dy Stanton & Susan B. Anthony” (1999). The film tells the story of these two friends who worked together decade after decade to obtain the vote for women, but who did not live to see their dream become reality. In fact, they died before my grandmother was born.

I watched the film by download from Netflix, which describes it saying, “Their fight for equality in a male-dominated society more than 100 years ago gets the exhaustive and respectful treatment it deserves in this film directed by gifted documentarian Ken Burns.”

As the article and film demonstrate, questions about biblical translation and interpretation arose long before second-wave feminism.