Blog & Resources

Looking for my thoughts on everything from bioethics to movies? You came to the right place. And while you’re here, check out my free downloadable resources.

Sign up to be notified when new posts release.

Church History: What Do We Learn about Women in Public Ministry?

“It was the feminist teachings of the past few decades that first spurred Christians to try to argue for [women in public ministry]. Like it or not, the two schools of thought are intertwined.” – Christian blogger

“The role of women in church ministry was simply not a burning question until it asserted itself in recent decades in conjunction with the modern women’s movement” – Men and Women in Ministry: A Complementary Perspective,p. 20

When I took some doctoral courses in history, I read numerous primary documents which revealed that the question about women in public ministry in the church has been burning since long before the U.S. Women’s Movement. So, I set out to determine when it actually started.

I thought maybe it began with the American and French Revolutions with the cry for individual rights. But then I read documents like the pamphlet that Margaret Fell Fox (think George Fox of Quaker fame) wrote in 1666 titled “Women’s Speaking Justified, Proved, and Allowed by the Scriptures.” And I saw art like the above engraving dated to 1723 that features a woman preaching.

So, I looked earlier. Maybe the Reformation started it, I thought—with its emphasis on the priesthood of all believers and the involvement of early women reformers like Katherina Zell.

But then I found writings like those of Christine de Pizan, who was born in the 1300s. Her work, The Book of the City of Ladies, presents a positive view of the Bible as she cites examples of biblical women, carefully selecting those who challenge her culture’s misogynistic ideals.

I kept going. Here are some samplings from the first nine centuries:

Pope PaschalI [Rome – West, AD 822] had a mosaic made of his mother, Theodora, labeled with the title “episcopa” (bishop). An inscription in another place in the same church (St. Praxedes) also describes her as “episcopa.”

Council of Trullo, Constantinople [Turkey – East], AD 692, canon 14. The Council speaks of “ordination” [cheirotonia] for women deacons using the same term used for ordination of priests and male deacons.

Synod of Orleans AD 533, canon 17 [France – West]. Attended by 32 bishops. Here’s a quote from the Synod: “Women who have so far received the ordination to the diaconate against the prohibitions of the canons, if it can be proved that they have returned to matrimony, should be banned from communion.”

St. Remigius of Reims [AD 533 AD, France] makes mention of his daughter, the deacon(ess) Helaria, in his will.

Synod of Epaone, AD 517, canon 21 [France]. “We abrogate the consecration of widows whom they call ‘deaconesses’ completely from our region.”

Ecumenical Council of Chalcedon, [East – Turkey] canon 15, AD 451. An earlier minimal age of 60 years for women deacons was relaxed to 40 years. The earlier practice was based on 1 Timothy 5:9: “Let a widow be enrolled if she is not less than sixty years of age.”

Synod of Orange, [West – France] AD 441, canon 26. Attended by 17 bishops. “Altogether no women deacons are to be ordained. If some already exist, let them bend their heads to the blessing given to the (lay) people.”

First Council of Nicea, [Turkey – East] canon 19, AD 325. Deacon(esse)s are mentioned in passing in a canon referring to the reconciliation of ex-members of the sect of Paul of Samosata (AD 260–272). Paul, patriarch of Antioch, denied the three Persons of the Trinity: “In this way one must also deal with the deaconesses or with anyone in an ecclesiastical office.”

Back, back, back I went. And each century sent me to an earlier one to find when it started. Eventually, I concluded that evidence for orthodox Christians affirming women in public ministry started on the day of Pentecost.

So what happened after that? What led to the changes?

This fall, I have been camping out in the first six centuries of church history, tracing the office of widow, which I first saw years ago mentioned in my Greek lexicon (BADG) as the last entry for the meaning of “widow.” It appears that the early church did have such an office, along with that of deacon(ess).

In 1976, a scholar in Belgium named Roger Grayson published a book titled The Ministry of Women in the Early Church with The Order of St. Benedict. It was translated into English and published by The Liturgical Press—not exactly feminist credentials. And he traces the offices of widow and deacon(ess) through the early centuries of the church. After surveying the data, he draws this conclusion: “Up to the end of the nineteenth century, historians of the early Church often identified deaconesses and widows as if these two different titles corresponded, for those who held them, to the same function.” In other words, historians conflated the two offices of deacon(ess) and widow. He goes on to note that “since deaconesses and widows obviously corresponded to quite different institutions, one can only wonder, after a close study of all the evidence, at the persistence of such an error” (110). That is, how is it possible that—in light of such overwhelming evidence—the error of conflating the two so stubbornly persisted?

Before exploring the answer, we need to keep in mind two details:

First, there was no female form of the word “deacon” in the early church and for some centuries to follow, in the same way that the word “teacher” in English does not indicate gender (e.g., teacher/teachess). That’s why I’m denoting uses of the word in this post as “deacon(ess)” unless the word “deaconess” appears in someone else’s quote.

Second, I’m using “office” to refer to positions in the church that have come with qualifications of character, as contrasted with “gifts,” which are bestowed by the Spirit on all believers.

Now then, apparently, historians expanded their tools of analysis beyond church fathers’ manuscripts and pronouncements by councils to include liturgies and tombstones for mentions of “deacon(ess)” in the early church. Yet in some places, we don’t even begin to find mention of “deacon(ess)” till the third century because the prominent office in that geographical location was “widow.” And the office of deacon(ess) looked different from the office of “widow” in the first centuries. And how the clergy was even configured varied by location (east as compared with west), century, and local council.

As Grayson has noted, such historians were not looking for references to the office of “widow.” Thus, some concluded that women’s membership in the clergy was a late development. Because if someone is thinking the word “widow” refers only to a woman bereft of her husband rather than also including an office rooted in 1 Timothy 5, that researcher can see a tombstone that says “a widow of the church” and miss that he or she is looking at the very evidence sought. Consequently, some historians have drawn faulty conclusions.

Grayson summarizes: “One thing is undeniable: there were in the early Church women who occupied an official position, who were invested with a ministry, and who, at least at certain times and places, appeared as part of the clergy. These women were called ‘deaconesses’ and at times ‘widows’” (xi).

May I remind the reader that Grayson was writing in the 1970s for a Roman Catholic publisher in a different country? This is not US feminism in the Protestant church talking.

The history of women in public ministry reveals that it started at the beginning. And practices in the East differed from those in the West.

In some locations, the widow was 60 years old or older, and the virgin was younger. Tertullian [b. AD 160, N. Africa] ranked the widows among the clergy, and spoke of seats being reserved for them. In his work titled De virginibus velandis (9:2–3) he wrote with displeasure, “I know plainly that in a certain place a virgin less than twenty years old has been placed in the order of widows (in viduatu)!” Clearly, in this instance a “virgin” is not simply a maiden, but someone consecrated to Christ for vocational ministry.

In the East, deacon(esse)s catechized women considering conversion, assisted at baptisms for women converts, and distributed the Eucharist to female shut-ins. The ordination rites for deacons and deacon(esse)s were almost identical.

By the third century in the West, the office of widow was described as a thing of the past. Grayson notes that whenever the Alexandrians [i.e., Egypt—West] mentioned women deacons or widows, they referred to these as offices of the past, not active in the present. Both Clement and Origen occasionally recognized that women were placed in the service of the church in the time of the apostle Paul, but these men did not indicate that the office survived.

In the fifth century the Testamentum Domini Nostri Jesu Christi, probably from Syria [East], devoted four long chapters to widows. It referred to the “ordination of widows,” in two instances using the same word employed for clerics in major orders.

Later in the East, the relationship between widows and deacon(esse)s makes a reversal, and widows, who had once supervised deacon(esse)s become subject to deacon(esse)s.

Eventually, offices in the East have the same labels as in the West, but in the West they are merely honorary. The East was actually more conservative and segregated, so we find more mentions of workers doing ministry focused exclusively on women. For men to do so would have been considered an encroachment beyond their boundaries. But as infant baptism eventually replaced adult baptism, the need for someone to assist with female adults being baptized (often nude to symbolize “rebirth”) disappeared.

What other factors besides infant baptism led to the tapering off of women in ordained ministry?

These reasons emerged from the writings:

Rise of the all-male priesthood in the pattern of the Old Testament. (What happened to the NT priesthood of all believers?)

A return to Old Testament temple practices—especially after Constantine, with church buildings and the clergy/laity divide—such as barring menstruating women from worship. (What happened to the veil being ripped and the Law being replaced by Christ?)

Anthropology. Some of the church fathers held to Greek views (think Aristotle) of woman’s nature, which would be unanimously denounced today. (Why pattern the church’s practice after the thinking of a pagan philosopher?)

Misogyny. Many believed women were weak, fickle, lightheaded, of mediocre intelligence, and a “chosen instrument of the devil.” (Does that sound at all like Jesus?)

Regardless of what conclusions we draw about what of today’s practices should build on tradition and what need to go, we must never think that the US Women’s Movement was ground zero for the public, vocational, ordained ministry of women in the church. When we say such things, historians roll their eyes. If we talk only of what the church fathers were doing without including what the women were doing, we are talking only about “men in church history,” not “church” history.

It was not the feminist teachings of the past few decades that first spurred Christians to argue for women in public ministry. Like it or not, it started at Pentecost. And it will be fully realized in the eschaton (Joel 2, Acts 2).

On Feminism and Evangelicalism

As part of my PhD research, I read Betty Friedan, heard Gloria Steinem in person, and spent a bunch of semesters exploring the history and teachings of feminism. And after I did so, I reached the conclusion that evangelicals in general need to pull back and regroup both in our representations of feminists and in our approach to reaching them.Just as there is not one "Christianity" but many Christianities (e.g., Orthodox, Catholic, Anglo-Catholic, Protestant, Lutheran, Armenian, Calvinist), there are many feminisms (liberal, radical, Marxist, socialist, lesbian, biblical, difference feminists [we are women—viva le difference! from men] and sameness feminists [we’re the same except for biology]), and more.Liberal feminists came out of the Equal Rights Movement. Betty Friedan was one of them. They are interested in equality, not to be confused with sameness. That is, they want the law to quit “seeing gender,” i.e., being biased against one sex or the other in terms of job opportunities, pay, child custody, and property ownership, for example. These feminists were never for unisex bathrooms, though I myself claimed they were in a scathing article I wrote against the ERA in college. I was wrong.Liberal feminism is concerned with attaining economic and political equality within the context of a capitalist society through reforming, improving, and changing existing systems. In Betty Friedan’s book, The Feminine Mystique, she gave voice to women wanting more for themselves than domestic tasks that had been stripped of much of their interesting work (which had long since been shipped off to factories) in such a society. Many Christians describe her as demeaning the vocation of homemaking, but that is not a fair representation. Friedan challenged the misogynistic presuppositions of Freudean psychoanalysis, arguing that women did not envy men’s penises, but rather their opportunities.[i] A woman should not have to be a homemaker, she felt, if said woman doesn’t want to be one. And if she is one, she should not be told that her children are her entire identity.The number of books sold—three million in its first three years in print[ii]—demonstrated that Friedan had given voice to what many felt.The radical feminists, on the other hand, came out of the Peace Movement. They saw and see so much wrong with materialism/capitalism that they think we will never have equality under the law. Solution? Overhaul society. Radical feminism focuses on patriarchy as the main cause of women’s oppression and operates on the belief that the system is too deeply ingrained and corrupt to modify, so must be radically overthrown. So forget the liberals’ efforts to modify existing laws and work within the system. Radicals want to make noise, shake it up.That's why so many in this group are also big into environmentalism, sometimes Marxism, sometimes socialism, peace, and no nukes. A radical feminist professor of mine said to me, “There is much in Christianity that would oppose materialism too, right?”As the waters of second-wave feminism have receded, numerous puddles have remained, but every resulting feminism challenges some aspect of social, political, or economic structure.The different strains break down as follows:

Liberal – Individual rather than collective. Seek reform, not revolution. Liberal feminists work within a capitalistic system, laboring to change laws to provide equal opportunities for males and females. A liberal feminist measures progress in the numbers of women and men occupying positions previously considered male-only or female-only. Liberal feminism is the most “mainstream” form of the many feminisms. While socialist feminists focus on collective change and empowerment, liberal feminists focus on individual change and empowerment. Liberal feminists tend to minimize gender differences, not necessarily from a belief that they don’t exist but from a belief that they shouldn’t matter legally.

Radical – Collective rather than individual. Seeks revolution, not reform. Radical feminists believe the only way to achieve gender equality is to overhaul society. They see male domination of women as the most fundamental form of oppression, and they focus on understanding how men obtain and use power. Because radical feminism shares with socialist feminism the commitment to dramatic social change, radical feminism is often grouped with socialist feminism. Radical feminists view society as patriarchal and believe patriarchy must be transformed on all levels.

Cultural – A subset of radical feminism is cultural feminism. Cultural feminists maximize gender differences. They tend to stress attributes associated with women's culture (e.g., caring, relationships, interdependence, community), insisting these attributes must be more valued. They reject what they consider unisex thinking in favor of affirming women’s essential femaleness. They tend to de-value virtues typically attributed to men such as domination, autonomy, authority, and independence.

Socialist feminism – Collective rather than individual. Seek revolution, not reform. Whereas liberal feminists focus on empowering the individual, socialist feminists seek collective change and empowerment. Socialist feminists believe that capitalist societies have fundamental, built-in hierarchies, which result in inequalities. Thus, it's not enough for women individually to rise to powerful positions; instead power must be redistributed. True equality, they believe, will not be achieved without overhauls—especially economic overhauls.

Marxist or materialist feminism – Collective rather than individual. Seek revolution, not reform. While generally opposed to Socialism, Marxist feminists have much in common with socialist feminists. Marxist feminism is based on Marxist views of labor reform. Like socialist feminists, they believe capitalism is the root of the problem, and power must be redistributed.

Womanists – The mid-seventies saw the rise of womanism. Womanists emphasize women’s natural contribution to society (used by some in distinction to the term “feminism” and its association with white women). Womanists see race, class, and gender oppression as so interconnected that those who seek to overturn sex and class discrimination without addressing racism are themselves operating out of racism. And they tend to view arguments about whether moms can work as white, middle-class concerns.

Whatever the form, the vast majority of those seeking women’s equality are not man-haters. I heard Gloria Steinem say that one of her greatest frustrations is that she has been accused of being a man-hater, and she is most adamantly not, nor has she ever been. In fact, she said the saddest letters she receives are from male prison inmates empathizing with women who have been raped/oppressed, because they these men are finding themselves victimized behind bars, and they now identify with the suffering.See why I bristle when I hear evangelicals talk about “the feminists”?[i][i] Betty Friedan. The Feminine Mystique. (New York, NY: Dell Publishing Co., Inc., 1963. See especially the chapter titled, “The Sexual Solipsism of Sigmund Freud.”[ii] Source: Ben Wattenberg, “The First Measured Century,” PBS.

Lean In ≠ Keep Others Down

Recently the NY Times ran an article titled "A Feminism Where Leaning In Means Leaning on Others." The author, Gary Gutting, interviewed a feminist who was critical of Sheryl Sandberg and her approach to business in her book Lean In (reviewed on this site). The interviewee was Nancy Fraser, professor of philosophy and politics at The New School. She is the author of Fortunes of Feminism: From State-Managed Capitalism to Neoliberal Crisis. Fraser said, "For me, feminism is not simply a matter of getting a smattering of individual women into positions of power and privilege within existing social hierarchies. It is rather about overcoming those hierarchies. This requires challenging the structural sources of gender domination in capitalist society—above all, the institutionalized separation of two supposedly distinct kinds of activity."First of all, this interchange provides a good example of how liberal feminists and radical feminists differ in their approaches—as different as Protestants and Roman Catholics. The liberal feminist works within the system to bring justice; the radical thinks the whole male-dominated system is corrupt and nothing short of revolution will fix this. A subset is Marxist feminism, which has as its special focus capitalism and work.Now then, I think it's unfortunate that Fraser summarizes Sandberg as trying to get more women into corner offices. The end result of her counsel may be just that. But the goal is not to make all working women CEO's and COOs. Indeed, Sandberg is in no way down on being a stay-at-home mom, nor is she oblivious to those of lower socioeconomic class.Lean In was written to the working woman. Its examples include mostly women of middle- to upper-class socioeconomic status, because that is where the author lives; but she does not call all women to have that status. The woman I know who cleans houses —Lean In's principles apply to her too. If she needs to charge more because the value of her work has gone up, she benefits from Sandberg's wise job counsel. If this woman needs a mentor to help her grow her business, she benefits from Sandberg again.The book was not just about gaining corporate power or having a certain kind of job. It was not even saying a woman has to be in the corporate world to get ahead. This is a common criticism of feminism—that it undervalues the non-corporate woman's work. But that is an unfair characterization. A stay-at-home mom needs the same principles. She needs to know how to avoid shrinking back. To learn to be unafraid of asking for something. If she needs a respite day—if she needs to do some self-care—ask for it. Plan for it. Know what she needs and not fear that doing so is unfeminine or selfish or that she is unworthy of it.Yes, Sandberg leans on others. But she also pays them for their services. And every employed person being paid benefits from the same principles, regardless of where their work falls in the food chain. Just because some have more social power in their work—that does not mean the job they hold is the ideal. As I said, Sandberg does not expect everybody to become a CEO or a COO. What she does believe is that women can do a better job of strategizing and sitting at the table—including asking for what we need to meet any jobs' demands.

The Other F-Word (Feminism)

I have read Betty Friedan's The Feminine Mystique and heard Gloria Steinem in person. And I spent some years in the halls of academia exploring the history and teachings of feminism. The result: I've concluded that most Christians need to pull back and regroup both in our representations of feminists and in our approach to engaging them.

Just as there is not one "Christianity" but many Christianities (Orthodox, Catholic, Anglo-Catholic, Protestant, Lutheran, Armenian, Calvinist, Reform, dispensational, etc.), there are many feminisms (Marxist, socialist, radical, liberal, lesbian, biblical, difference feminists (we are women—viva le difference! from men) and sameness feminists (we're very similar to men).

Those who self-label as liberal feminists come from the equal rights movement. Betty Friedan was one of them. They are interested in legal equality, not to be confused with sameness. They want the law to quit seeing gender when they approach job opportunities, pay, child custody, property ownership, etc. They were never for unisex bathrooms, though I myself claimed they were in a scathing article I wrote against the ERA in college. I was wrong.

And they are not at all man-haters. Not. At. All. About five years ago, I was present when Gloria Steinem said that one of her greatest frustrations has been that she is accused of being a man-hater, and she is most adamantly not, nor has she ever been. In fact, she said the saddest letters she receives are from male prison inmates empathizing with women who have been raped/oppressed, because they are finding themselves victimized behind bars and they identify with the suffering now.

Those who refer to themselves as radical feminists came out of the peace movement. They see so much wrong with materialism/capitalism that they think we will never have equality under the law. Forget trying to change the law, they say—we need to overhaul society. Make noise. Shake it up. That's why many in this group are also big into environmentalism, sometimes Marxism, sometimes socialism, peace, no nukes, etc. But as a radical feminist professor asked me, "There is much in Christianity that would oppose materialism too, right?"

We need to ask people, "What do you mean when you use that word?" We might be surprised.

The Feminists We Forgot: My Post for Her.Meneutics

Last week Christianity Today's women's site, Her.Meneutics, ran my piece on women's history to close out their extended focus on Women's History Month. Check out The Feminists We Forgot.

Is Peter Insulting Women? (Part 1)

My Tapestry post for the week:

Secret Thoughts of an Unlikely Convert

"I was a broken mess. I did not want to lose everything that I loved. But the voice of God sang a sanguine love song in the rubble of my world."

Whilein her thirties, Dr. Rosaria Champagne held a tenured position at SyracuseUniversity, owned two houses with her lesbian partner, modeled hospitality tostudents, and rescued abandoned and abused dogs. An English professor withexpertise in Feminist Studies and Gender Studies, she tried to live ethically and enjoyed classroomsbursting with students eager to hear her speak. But then she encounteredsomething that turned her world upside down: Christianity. And the experiencefelt anything like “a wonderful plan.” In her words, it felt more like “a trainwreck.”

Miss Representation

Tonight we watched an 88-minute documentary, Miss Representation, about how the media's often disparaging portrayals of women contribute to the under-representation of females in positions of high responsibility, creating another generation of women defined by beauty and sexuality, and not by their capacity as leaders.

Controversial. Thought-provoking. A real discussion-starter.

The Feminine Mystique at 50: A Response

A Podcast in Which I Spout Off about Feminism, Sexism, and Gender

The Driscolls on Stay-At-Home Dads

Have you seen this clip from the Driscolls? I sent it to my class on the Role of Women in Ministry, and here is the response from one of the guys, John Lavoie, whose wife is working so he can go to seminary:

I watched the clip with my wife Rachel last night and we talked about it for a little bit.

What do you think?

Is My Husband My Priest?

My post on the Tapestry blog this week:

One so-called feminist idea that we might think came out of the Enlightenment actually came right out of the Reformation: The doctrine of the priesthood of all believers. This teaching opened new ways for men and women to think of women not as intrinsically inferior to men, but as partners called to lead the world to Christ.

In Peter’s first epistle we read, “But you are a chosen race, a royal priesthood (italics added), a holy nation, a people of his own, so that you may proclaim the virtues of the one who called you out of darkness into his marvelous light” (2:9). Peter was writing to the whole church, not to men only, when he described all his readers as priests. His phrasing harkens back to God’s desire for Israel that they would “be for me a kingdom of priests and a holy nation” (Exo. 19:6). God was speaking to men and women there, too.

Meanwhile, in the apostle Paul’s first private correspondence with his protégé, Timothy, he wrote this: “For there is one God and one intermediary between God and humanity, Christ Jesus, himself human.” Some translations say “one intermediary between God and man…” but the word translated “man” here is “anthropon,” a form of the word from which we get “anthropology”—the study of humans. And in this context Paul had in mind humans, not males only. Humans have direct access to God through Jesus Christ. No human other than the man Christ serves as an intermediary. We can be priests, leading people to God. But we do not stand between the people and God. And that includes husbands standing between God and their wives.

So how might that look in the home? Let’s say, for example, a godly husband thinks that he and his wife should abstain from intimate relations for a time so they can devote themselves to prayer. If he were her priest, he might initiate the conversation and guide her, listening to her input, but then informing her of his benevolent final decision. But if we look at how Paul counseled the Corinthians, we read that such a picture is less than ideal. Because the wife has authority (v. 7, root: exousia) over her husband’s body just as much as he has authority over hers—a radical idea in those days, and a serious challenge to Roman views of masculinity (and perhaps of contemporary ones, too). Paul writes, “Do not deprive each other, except by mutual agreement…” (italics added). So in our example, which happens to match the one example we have in the New Testament of a couple making a decision related to spiritual things, we see the husband and wife are partners. Equals. Sharing authority in spiritual decision-making. And like friends deciding where to eat dinner, neither needs 51 percent of the vote. Paul assumes a spiritually mature couple can decide mutually what is best. No one takes on the role of priest in the sense of mediating. If the two come to an impasse, the husband does not say, “I am charged with guiding you spiritually, so here is my decision.”

Yet sometimes people read that the husband is head of the wife, his body, and they see in such language a picture of an intermediary. Some even describe the husband as the priest in the home. I once interviewed Eugene Peterson, best known for The Message, and he confided, “At a pastor’s conference I told those in attendance that at noon on Mondays, our Sabbath/hiking day, [my wife] prayed for lunch. In fact I think I said, ‘I pray all day Sunday. I’m tired of it. She can do it on Monday.’ There was one woman there who was really irate. She said I should be praying and Jan should not be praying because I’m the priest in the family and she’s not the priest. That’s silliness. You are brother, sister, man, wife, friends in Christ. You work out the kind of relationship before the Lord that is intimate. And no, I don’t think there’s any kind of picture you have to fit into, that you have to produce. That’s oppressive isn’t it? After all, this is freedom in the Lord.”

For some of us, it’s time to “woman up” and take responsibility for our own spiritual lives. Sometimes a wife will shirk responsibility for her walk with Christ and blame it on her husband’s failure to initiate as a spiritual leader. But every woman who is “in Christ” is a priest who will stand before God and give account for herself. And that idea is not coming out of feminism. It’s right out of the holy Word of God.

It's Not Some New Debate

The cover story for this month's issue of Christianity Today relates to the 400th anniversary of the King James Version of the Bible. In "A World without the KJV," Mark Noll writes, "American history might have skipped several dark chapters if the KJV had not become the dominant Protestant translation. Many of the worst chapters concern slavery. The KJV regularly rendered the Greek word doulos as 'servant.' 'Servant' and the more accurate translation, 'slave,' were already differentiated in the 16th century and became even more so as time passed… These passages regularly trumped efforts to use biblical reasoning rather than straight biblical quotation….

The cover story for this month's issue of Christianity Today relates to the 400th anniversary of the King James Version of the Bible. In "A World without the KJV," Mark Noll writes, "American history might have skipped several dark chapters if the KJV had not become the dominant Protestant translation. Many of the worst chapters concern slavery. The KJV regularly rendered the Greek word doulos as 'servant.' 'Servant' and the more accurate translation, 'slave,' were already differentiated in the 16th century and became even more so as time passed… These passages regularly trumped efforts to use biblical reasoning rather than straight biblical quotation….

"Women made similar complaints throughout the 19th century. What we would call feminist objections were of two kinds. Some objected to the whole character of biblical revelation, in whatever version. Many contributors to Elizabeth Cady Stanton's The Woman's Bible of 1895 made such complaints. Others were more concerned with issues of translating the words for "man" and "mankind," issues that still incite debate. In 1837, abolitionist and suffragist Sarah Grimké had these issues in mind when she professed her entire willingness to live by the Bible, but also her ardent desire for a new translation: ‘Almost every thing that has been written on this subject, has been the result of a misconception of the simple truths revealed in the Scriptures, in consequence of the false translation of many passages of Holy Writ …. King James's translators certainly were not inspired. I therefore claim the original as my standard, believing that to have been inspired."

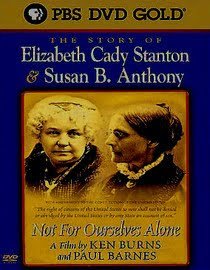

Tonight I watched the three-hour PBS documentary, “Not for Ourselves Alone: Elizabeth Ca dy Stanton & Susan B. Anthony” (1999). The film tells the story of these two friends who worked together decade after decade to obtain the vote for women, but who did not live to see their dream become reality. In fact, they died before my grandmother was born.

dy Stanton & Susan B. Anthony” (1999). The film tells the story of these two friends who worked together decade after decade to obtain the vote for women, but who did not live to see their dream become reality. In fact, they died before my grandmother was born.

I watched the film by download from Netflix, which describes it saying, “Their fight for equality in a male-dominated society more than 100 years ago gets the exhaustive and respectful treatment it deserves in this film directed by gifted documentarian Ken Burns.”

As the article and film demonstrate, questions about biblical translation and interpretation arose long before second-wave feminism.

Liberals Are Not Radicals

....that is, if we're talking about feminists. Just as there are many denominations within Christianity, there are different strains of thought within feminism. And sometimes they vehemently disagree with each other. The four major schools break down as follows:

• Liberal – Focus is individual solutions rather than collective. Seek reform, not revolution. Liberal feminists work within a capitalistic system laboring to change laws to provide equal opportunities for males and females. A liberal feminist measures progress in the numbers of women and men occupying positions previously considered male-only or female-only. Liberal feminism is the most “mainstream” form of the many feminisms. While socialist feminists focus on collective change and empowerment, liberal feminists focus on individual change and empowerment. Liberal feminists tend to minimize gender differences.

• Radical – Focus is collective solutions rather than individual. Seek revolution, not reform. Radical feminists believe the only way to achieve gender equality is to overhaul society. Forget passing laws here and there to make things equal. Go for revolution. Radical feminists see male domination of women as the most fundamental form of oppression, and they focus on understanding how men obtain and use power. Because radical feminism shares with socialist feminism the commitment to dramatic social change, radical feminism is often grouped with socialist feminism. Radical feminists view society as patriarchal and believe patriarchy must be transformed on all levels.

A subset of radical feminism is cultural feminism. Cultural feminists maximize gender differences. They tend to stress attributes associated with women's culture (e.g., caring, relationships, interdependence, community), insisting they must be more valued. They reject unisex thinking in favor of affirming women’s essential femaleness. They tend to de-value virtues typically attributed to men such as domination, autonomy, authority, and independence.

• Socialist feminism – Focus is collective solution rather than individual. Seek revolution, not reform. Whereas liberal feminists focus on empowering the individual, socialist feminists seek collective change and empowerment. Socialist feminists believe that capitalist societies have fundamental, built-in hierarchies, which result in inequalities. Thus, it's not enough for women individually to rise to powerful positions; instead power must be redistributed. True equality, they believe, will not be achieved without overhauls—especially economic overhauls.

• Marxist or materialist feminism – Focus is collective solution rather than individual. Seek revolution, not reform. While generally opposed to Socialism, Marxist feminists have much in common with socialist feminists. Marxist feminism is based on Marxist views of labor reform. Like socialist feminists they believe capitalism is the root of the problem, and power must be redistributed.

Additionally, the mid-seventies saw the rise of black or womanist feminism. A distinctively African-American version, this "less liberal" pool of feminism sees race, class, and gender oppression as interconnected. Womanist feminists believe that those who seek to overturn sex and class discrimination without addressing racism are themselves operating out of racism. A key text for them is the 1792 work by Mary Woolstonecraft, Vindication of the Rights of Woman.

Next time you talk to someone who calls herself a feminist, ask some questions. "Do you think that beyond physiology, men and women are essentially the same, or do you think there's something fundamentally different in maleness and femaleness?" "Do you think the solution is changing laws or full-on revolution?" You might have a fascinating discussion.

Mini Update

One of my interns, Kelly Stern, has some expertise in poetry--both knowledge of great poets and creation of her own works. So an added element in the class this summer is Kelly's fifteen-minute daily intro to poetry. Donne. T. S. Eliot. George Herbert. And especially the Welsh Christian poets who wrote over 1,000 years ago. Great stuff.

A former DTS student owns Texadelphia restaurant, and he offers free lunches to any faculty member who shows up with up to three students. So we've had the added benefit of yummy free lunches together in small groups. What's not to love about that? An educator's dream.

In the midst of this, I managed to finish my reading list for the women's history portion of my PhD exam prep. The last work was Betty Friedan's The Feminine Mystique. I had heard so many awful things about Betty and her book, that I almost expected to find a rant by a man-hating, housewife-dissing femiNazi. Instead I found a reasoned call to women having purpose in their lives. I found much with which I agreed, in fact. The number of women going to college dropped about 10 percent after the 1930s. And Fridan offers some interesting cultural reflections on why. (You can read her chapter on Freud's sexual solopsism here.)

Also, context is everything. When Friedan said homemakers asked, "Is this all?" she didn't mean to suggest caring for one's family is the occupation of losers. She suggested (and her sales indicate she was spot on) women were asking "Is this all" on a more cosmic level. As in--Can complete fulfillment as a human being come from cocooning with the hubby and kids?

My take is that Friedan thought the world needed women's involvement, and women themselves needed community and world involvement, right along the lines of "She stretches forth her hand to the needy and the teaching of kindness is on her tongue" (see Prov. 31). And beyond that, women need eternal purpose--the kind Rick Warren wrote a bestseller about. The kind which all humans need--a purpose that reaches beyond their own temporal lives. And seriously, Friedan was no man-hater. ("Man is not the enemy here. But the fellow victim.") She said she didn't hate men, only vacuum cleaners. Dare I say I agree on that score?

What I read made me wish we (especially the Christian sub-culture) had done a better job of listening and responding to her. And finding points of agreement. I wish we had acknowledged the emptiness of so many and encouraged them to find their purpose in the One who made them and granted them the job of co-regent over the planet. And to develop their spiritual gifts. And to take their kids with them as they served a broader community. And I wish we had affirmed each women seeking a skill, so if she were single or widowed, she would have some security against poverty. It seems to me these would have been much more constructive responses than vilifying the journalist who reported what she saw.